2/11/2014

RE: Taking action against gender-related killing of women and girls

UNDERSTANDING AND PREVENTING BURN AND ACID ATTACKS ON WOMEN

Report Prepared by

Professor Mangai Natarajan PhD John Jay College of Criminal Justice,

The City University of New York, USA

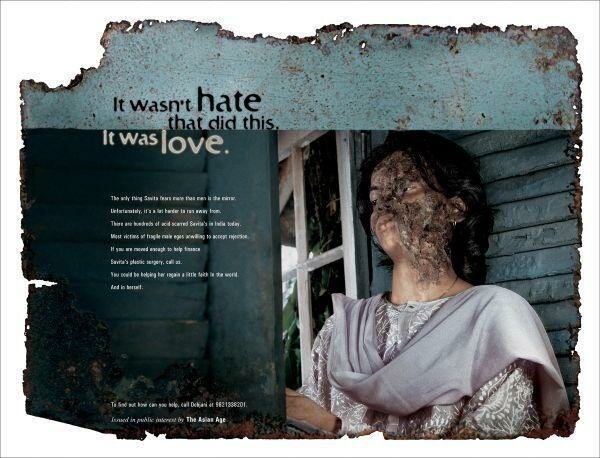

The United Nations defines violence against women as any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life. According to the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), violence against women and girls takes many forms — from the most universally prevalent forms of domestic and sexual violence, to harmful cultural practices including abuse during pregnancy, honor killings, female feticide and infanticide, and dowry deaths. Acid or burn attacks on women which involve pouring acid or igniting kerosene on their faces and bodies is one of the most severe forms of such violence. In Indian subcontinent, kerosene is widely used as the fuel for cooking and concentrated acid is used to sterilize kitchens and bathrooms and so they are easily and readily available. With just a few rupees, therefore, anyone can buy a weapon that can ruin another person’s life in just a few seconds (BBC News). Such attacks are commonly used to terrorize and subjugate women and girls in a swath of Asia from Afghanistan through Cambodia (Kristof 2008). The attackers are rarely prosecuted and such attacks occur in many parts of the developing world especially in South Asia including India (Das et al, 2013; Virendra 2009; Dasgupta, 2008; Natarajan, 2007; Natarajan 1995; Chowdhury, 2005; Sharma, 2005; Maghsoudi et al., 2004; Kumar and Tripathi, 2003; Swanson, 2002; Sharma, Dasari, and Sharma, 2002; Swanson 2002; Sweeney and Myers-Spiers, 2000; Faga et al., 2000; Dugger, 2000; Sawhney, 1989; Dasgupta, and Tripathi, 1984). Despite improvements in medical facilities for treating these victims they often endure severe disfigurement and life long suffering. The feelings of rejection at all levels of their lives lead many of these women to commit suicide.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year there are 195,000 deaths resulting from burns, and approximately 10 million serious injuries. A large proportion of these incidents occur in developing countries and that India alone probably has 200,000 deaths annually from burns. According to Peck (2012) a significant number of burns and deaths from fire are intentional[1] and self-immolation in low-income countries is decidedly more common among women than men in India. These estimate perhaps an underestimated reporting or recording of intentional burns due to the ways in which the reported cases are dealt by the health care and law enforcement system.

Most of the existing documents on the topic of acid and kerosene burn attacks are media accounts and agency reports that call for government action. However, some recent studies have begun to document the problem in more detail. Sharma’s (2005) study of unnatural deaths found that the male to female ratio was 1:3 for burns, 2.6:1 for poisoning and 1.4:1 for other methods. Other studies find that about three quarters of all burn victims are females of whom more than 80% are married (Kumar, and Tripathi,2003;Sharma, Dasari, & Sharma, 2002; Rao, 1997; Jayaraman , Ramakrishnan and Davies, 1993;Kumar, 1991). In a recent comprehensive report based on multiple health data sets, Sanghavi, Bhalla and Das (2009) report that of the 163,000 fire related deaths in the records, 106,000 were women between 15 and 43 years of age. These fire-related deaths were due to kitchen accidents, self-immolation, and domestic violence (Kumar, and Tripathi, 2003;Sharma, Dasari, & Sharma, 2002; Rao, 1997; Jayaraman , Ramakrishnan and Davies, 1993; Kumar, 1991). A study (Ganesamoni Kate and Sadasivan, 2009) of 177 consecutive adult admissions to a hospital in Southern India for treatment of burns injuriesfound that the mortality rate in females with burns (71.4%) was much higher (46%) than that for men. It also found that facial injury increases the risk of death fourfold for women.

Studies are entirely lacking that interview the victims of this violence, not just because of lack of funding for research, but also because it is hard to gain access to interview the victims. Many victims are ashamed and may not want to see or talk to anyone other than their doctors or social workers. Many do not want to talk about their traumatic experiences to strangers. Most importantly many women who have been burned do not survive the attacks or are too disabled to participate in surveys (Garcia-Moreno2009).

This essay presents the findings of a recent empirical research (Natarajan 2014) that provides a comprehensive approach to improve the theoretical understanding of burns attacks with the ultimate purpose of prevention. The focus on prevention helped to determine the choice of the theoretical framework for this research which is discussed below.

Violence against women is a complex phenomenon that has been explained from a variety of perspectives including general systems theory, resource theory, exchange or social control theory, and the subculture of violence theory (Jasinski, 2001; Felson, 2002). Feminist scholars have focused on the concept of patriarchy, which evokes images of gender hierarchies, dominance, and power arrangements in society (Hunnicut, 2009). A vast range of criminological theories that have generally sought to identify the social and psychological factors giving rise to delinquent or criminal dispositions Unfortunately these theories only imply long term solutions to the problem when burn attacks are an everyday occurrence in today’s society. Criminological theories which carry more immediate and practical policy implications are the rational choice perspective (Clarke, 1992; Clarke and Felson, 1993) and routine activity theory (Cohen and Felson, 1979; Felson, 1998, Felson and Clarke, 1998). These new group of criminological theories, crime opportunity theories, focus on the immediate context in which specific kinds of crime occur (Felson and Clarke, 1998). This helps to identify aspects of the situation that facilitate the commission of the crimes and that can be changed to make them less likely to occur (Wortley and Smallbone, 2006). This approach is known as situational crime prevention (Clarke, 2010)which has strong record of success with many different kinds of crime, including violent crimes. A pertinent example concerns injuries in pub fights in England. Analysis showed that many of these injuries were inflicted with beer glasses that were smashed to serve as weapons (Shepherd 1994). This finding led to a national campaign to replace conventional beer glasses with ones that that shattered into crumbs when broken.

With this criminological backcloth, using three months hospital registry data (N=768) in 2011/2012 and interviews with 60 women patients in the burns ward of a large city hospital in India the study indicate that the majority (65%) of intentional burns cases were women and, among cases with the most severe burns, more women than men died. Furthermore, interviews with women in the burns ward revealed that at least 20% of intentional burns were reported as accidents. This is because the hospital is required by the law to report any cases of intentional burns to the police for further investigation. Such investigations lead to delays in securing admissions for treatment even when the injuries are serious. Because the women’s families do not want police inquiring into their domestic problems, they report suicides and homicides as accidents. Victims concur because they may be afraid of the perpetrators, often their husbands, and they also fear that, if their husbands are arrested, their children will be left stranded on the streets.

These findings indicate that intentional burns, particularly those suffered by women, constitute a severe public health problem in India and most likely as well in similar developing countries. This exploratory study indeed found that: 1. the opportunity structures that facilitateintentional and accidental burns are similar, but intentional burns also involve other contributory factors, including husband’s alcohol abuse, verbal abuse and physical abuse, all common factors associated with domestic violence at home; 2. kerosene is the main agent because of its easy availability and accessibility in countries such as India where it is commonly used as fuel for stoves and lamps; 3. most intentional burns are self-inflicted though some appear to be attempted homicide; 4. most patients with intentional burns are young women in domestic situations; 5. there is a higher mortality and morbidity for women whose upper body is often deeply affected by the burns; 6. because of family pressure to avoid police inquiries, patients sometime report intentional burns as accidents. The findings suggest that a program of research integrating public health and criminological prevention approaches is needed to deal with this serious problem.

According to the women interviewed for this study, in many cases these intentional burns, whether homicidal or suicidal, arise from domestic conflicts. This was the case for both the main groups of cases revealed by the interviews: (1) women from disadvantaged communities who, as a result of feelings of rejection at all levels of their lives, attempted suicide by self-immolation; and (2) women whose family members (often the husband) ignited kerosene on them during domestic disputes. While some of the disputes were related to dowry problems (“bride burning”), a wider array of causes was revealed by the interviews with the women, including alcohol abuse by the husband or partner; verbal and physical abuse: quarrels over family matters and money, and the victim’s frustration and depression before the incident. Overall, these findings suggest that domestic violence in India, and probably in other similar societies, needs to receive the level of attention from the authorities that it now receives in many countries elsewhere in the world.

An important footnote to the above is suggested by the finding from the interviews that some of the women who self-inflicted burns did not intend to kill themselves, but intended only to signal their extreme distress. This finding suggests that the feasibility should be explored of developing a public information campaign, directed at girls and young women, concerning the terrible consequences of self-inflicted kerosene burns.

A further set of important findings also relates to kerosene, which was implicated in 70% of the present sample of intentional burns cases. Kerosene is widely used as a fuel for cooking and heating of stoves and lamps by the many millions of households in India without electricity. The part played by the wide availability of kerosene in accidental burns is widely understood and numerous efforts (including UN efforts) are underway to design “safer stoves”. However, designs to prevent accidental burns might not be sufficient for preventing intentional burns and additional ways to modify stoves (and the way that kerosene is stored in the stoves) might be needed. For example, kerosene might need to be bought and delivered to the stove (or other domestic appliance) in specially designed tanks such as used for delivering propane in many parts of the world. The stopper to these tanks should be designed to ensure that the flow of kerosene is only released when the tank is firmly in place in the stove. This would prevent kerosene from being poured over the head and body before it is ignited. It is important therefore that those developing safer stoves should also be cognizant of the need to employ designs that prevent the use of kerosene in intentional injuries.

Finally, the interviews with the patients revealed that, due to serious disfigurement of the face and upper body and the lack of social support from immediate family and community, many of the women victims, whether of intentional or accidental burns, were at serious risk of committing suicide on release. Unfortunately, the hospital has no resources for formal aftercare on discharge and there is a need for collaborative efforts with social service agencies and NGOs to provide counseling and aftercare for burns victims.

In sum, integrating public health, gender and criminological perspectives in developing preventive measures that include: risk assessment tools for treatment; safe designs for delivering and storing kerosene for domestic use; integration of these designs with global safe-stove initiatives; promoting awareness among young women and girls of the consequences of self-inflicted burns; and publicizing the need for effective policy responses including legislation, education and advocacy in saving lives should be an integral part in taking actions against gender-related killing of women and girls.

References

Chowdhury, E. H. (2005). Feminist negotiations: contesting narratives of the campaign against acid violence in Bangladesh. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, 6 (1),163-192.

Clarke, R.V. (1992). Situational crime prevention: successful case studies. Albany, NY: Harrow and Heston.

Clarke, R.V. (2010). Situational crime prevention: theoretical background and current practice. In Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Hall GP, editors (pp.271-283).. Handbook on Crime and Deviance. New York : Springer.

Clarke, R. V. and Felson, M. (Eds.) (1993). Routine activity and rational choice. Advances in Criminological Theory, Vol 5. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Das,K.K, Khondokar,S.M, Quamuzzaman, Ahmed,S.S, Peck,M. (2013). Assault by burning in Dhaka, Bangaledesh. Burns, 177-183.

Dasgupta, S. D.(2008), “Acid Attacks”, in Renzetti, C. M., Edleson, J. L., Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Violence, 1 (1st ed. pp. 5–6,), Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Dasgupta, S. M. and Tripathi, C. B. (1984). Burnt wife syndrome. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, 13(1), 37-42.

Dugger, C.A. (2000). Kerosene, weapon of choice for attacks on wives in India. New York Times, 12/26/2000, p1.

Faga, A., Scevola, D., Mezzetti, M.G and Scevola, S. (2000). Sulphuric acid burned women in Bangladesh: a social and medical problem. Burns, 26,701-709.

Felson, M. (1998). Crime and everyday life, Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Felson, M. and R.V. Clarke (1998). Opportunity makes the thief . Police Research Series, Paper 98. Policing and Reducing Crime Unit, Research, Development and Statistics Directorate. London: Home Office.www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/prgpdfs/fprs98.pdf

Ganesamoni S, Kate V, Sadasivan J. (2010). Epidemiology of hospitalized burn patients in a tertiary care hospital in South India. Burns, 36, 422-429.

Garcia-Moreno C. (2009). Gender inequality and fire-related deaths in India. Lancet, 373,1230-31.

Hunnicutt, G. (2009). Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women. Violence Against Women, 15(5), 553-573.

Jayaraman V, Ramakrishnan K.M and Davies, M. R. (1993). Burns in Madras, India: an analysis of 1368 patients in 1 year. Burns, 19, 339–44.

Jasinski, J. L. (2001) Theoretical explanations for violence against women. In C. M. Renzetti, J. L. Edleson, & R. K. Bergen (Eds.), Sourcebook on violence against women (pp. 5-22). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Kristof, N. D (November 30, 2008). Terrorism that’s personal. NY times Op- ed page.

Kumar, V and Tripathi, C. B. (2003). Fatal accidental burns in married women. Legal Medicine, 5 (3), 139-148.

Lester D, Agarwal K, Natarajan M. (1999). Suicide in India. Arch Suicide Res,5, 91–96.

Maghsoudi, H., Garadagi, A., Jafary, G.A., Azarmir, G., Aali, N., Karimian, B. and Tabrizi, M. ( 2004). Women victims of self-inflicted burns in Tabriz, Iran. Burns (03054179), 30 (3), 217-221.

Natarajan, M. (2014). Differences between Intentional and Non-intentional Burn Injuries inIndia: Implications for Prevention, Burns, http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0305-4179/PIIS0305417913004087.pdf

Natarajan, M. (Ed). (2007). Domestic violence: the five big questions. International Library of Criminology, Criminal Justice and Penology, Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Natarajan, M. (1995). Victimization of women: a theoretical perspective on dowry deaths. International Review of Victimology, 3(4), 297-308.

Peck, M. D. (2012). Epidemiology of burnsthroughout the World. Part II: Intentionalburns in adults. Burns, 38,630-637.

Rao, N. K. G. (1997). Study of fatal female burns in Manipal. Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, 14 (2), 57-59.

Roland, B. (28 July 2006). “Bangladesh’s acid attack problem“. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/low/world/south_asia/5133410.stm.

Sanghavi,P., Bhalla,K. and Das, V. (2009).Fire-related deaths in India in 2001: a retrospective analysis of data. Lancet www.thelancet.com Published online March 2, 2009 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60235-X

Sawhney, C. P. (1989). Flame burns involving kerosene pressure stoves in India. Burns 1989; 15: 362–64.

Sharma, B. R. ( 2005). Social etiology of violence against women in India. Social Science Journal, 42(3) 3, 375-389.

Sharma, B. R., Dasari, H. and Sharma, V . (2002). Kitchen accidents vis-à-vis dowry deaths. Burns, 28, 250-253.

Shepherd, J. (1994). Preventing injuries from bar glasses. British Medical Journal, 308: 932–933

Swanson, J. (Spring 2002), “Acid attacks: Bangladesh’s efforts to stop the violence.“, Harvard Health Policy Review 3, 3.

Sweeney, K. and Myers-Spiers, R. (2000).Bangladesh: acid-burn case awaits ruling.Off Our Backs, 30 (7), 4.

Virendra K. (2009). Dowry deaths (Bride burnings) in India. In Strengthening understanding of Femicide: Using research to galvanize action and accountability. Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), InterCambios, Medical Research Council of South Africa (MRC), and World Health Organization (WHO). Washington DC: .pp.89-94

Wortley, R., and Smallbone, S. (2006) (eds). Situational prevention of child sexual abuse. Crime

Prevention Studies. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

[1] Intentional burns are defined as “those in which the act that led to the injury has the purpose of causing harm”